Sustainable mining: Putting it as part of the discussions on charter change and sovereignty

Author’s note: This is a shorter version of a paper, which I submitted in my course work in Environmental and Natural Resources Management 233 – Rehabilitation of Marginal and Degraded Areas (November 2016), under the Master of Environment and Natural Resources Management program of the University of the Philippines.usta

In broad stroke

The Philippines is a very wealthy country when it comes to mineral resources. In 2014 and 2015 alone, the total (gross) production value from the mining industry amounted to more than 318 billion pesos. Economies including ours are indeed highly-dependent on mining. However, the extent of damage that mining operations cause certainly leaves a bitter after-taste in the mouth. This article takes off on the mining dilemma with focus on how development and remediation and rehabilitation works may be undertaken, anchored on the principles of sovereignty and sustainable development.

Why sovereignty, one might ask. It’s because we need to ensure that revenues from significantly extractive industries must always significantly flow back into the local economy. Whatever the chosen approach may be in the development and use of mining sites, rehabilitation plans must be in place and that they should first and foremost aim to allow nature to heal, through its natural recovery and succession processes. The development and rehabilitation plan must also be anchored on the appreciation of national patrimony, emphasizing the need to manage and benefit from our own resources. Foreign direct investments (FDI) are not necessarily evil. Most if not all economies certainly benefit from them. It is up to our economic managers to ensure that FDI and official development assistance are treated as additional and much-needed capital to fuel industries but not as a “sell-out” of our national patrimony.

It is hoped that this article will also be useful in guiding our policymakers and decision-makers in reviewing and amending the economic-related provisions in our Constitution, at the right time. At the minimum, charter change must be undertaken under a trustworthy leadership—and always, with the genuine representation of the people, where sovereignty resides.

I. Introduction

Damn if you, damn if you don’t.

This statement easily comes into mind when the word mining comes up. It is an economic activity that is often considered as a ‘necessary evil’—indeed, if love and money make the world go round, mining certainly makes it impossible for love and money to exist without it. For one, engagement proposals and wedding vows are sealed with a ring. Obviously, you are now enjoying your stay on earth because many years ago, your parents vowed to love one another and exchanged rings, which had been mined somewhere in the world, most likely in the rich soils and mountains of the Philippines. Of course, money has to be based in gold, which is also mined.

From sunrise to sundown and while humans sleep, they are dependents of this highly extractive industry. Can these humans even sleep without the comfort of air-conditioning and electric fans or the warmth of heaters? Indeed, one cannot imagine a world without mining.

This over-dependence, of course, comes with a price. In fact, when one looks at the horrors of mining, it is also difficult to imagine whether the concept of sustainable mining is even possible.

This article will not delve into the nitty-gritty of mining and the complexities of sustainable mining but rather share insights on why we need to assert more independence in the way we will develop, manage, and use our mineral resources. Second, for our previously-mined sites, our government should look at distinct strategies and interventions that are suitable for the Philippines. It is hoped that this article will lead to innovative work particularly with how the previous administration has taken important steps in monitoring and assessing the operations of mining companies in the Philippines.

II. Situational analysis

- Mining industry in the Philippines – a brief overview

The Philippines is a blessed country when it comes to mineral resources. In 2014 and 2015 alone, the total (gross) production value from the mining industry amounted to more than 318 billion pesos (MGB, 2016c). About 30% of the country’s thirty million hectares of land is estimated to host significant mineral deposits; currently, only about 3.8 percent is covered by mining projects (Hicks, 2013). Experts even estimate that the Philippines has the largest copper reserves in the world (Hicks, 2013). The Philippines is also endowed with significant deposits of other non-ferrous metals including gold, lead, nickel, silver, and zinc (US Geological Survey, 1997, as cited in Bravante & Holden, 2009). Mindanao, a well-endowed island, is said to host 48% and 83% of the country’s gold and nickel reserves, respectively (Visaya-Ceniza, 2015).

Current estimates put the value of the Philippines’ mineral resources at more than a trillion dollar (Hicks, 2013). This translates to more than 48 trillion pesos! Assuming that the country spends about three trillion pesos in a year, the country can live on mining alone for 16 long years (Figure 1).

Of course, no country in the world depends on mining alone so this figure only illustrates the significance of the Philippines’ mineral reserves. Just how much of this wealth really goes to the Filipino people, one is tempted to ask. This paper—while highlighting the rehabilitation aspect—will, hopefully, help in leading to some answers.

Meanwhile, the extent of the country’s mineral wealth and where these minerals are mostly found are in Table 1.

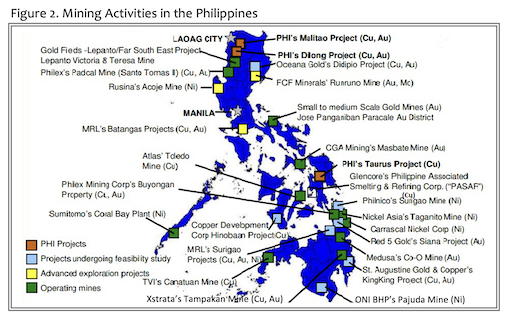

The map (Figure 2) shows the location of mining activities in the Philippines.

A check in the website of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau revealed that there are currently three hundred ninety seven (387) active mining agreements—categorized in six types of agreements—as of October 2016 (Table 2). This data and the information in Table 1 and Figure 2 show that mining activities are significantly done in many parts of the country.

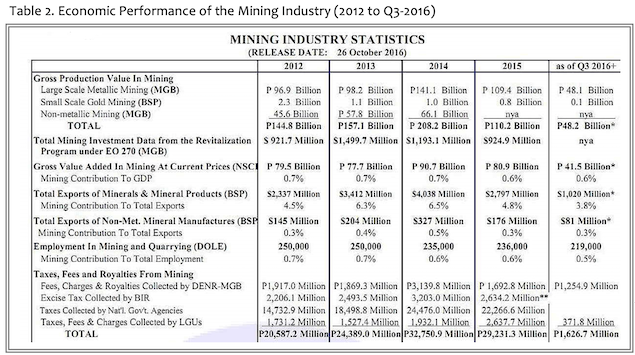

To appreciate how the industry is contributing to the economy Table 2 shows data from 2012 to the third quarter of 2016.

Again, it is not the intent of this article to give a thorough macroeconomic analysis but it can, hopefully, raise important points for further work. For instance, the economic value of the mining industry must be contextualized within social and environmental milieus. For example, are the economic benefits significantly higher (and more important) than the negative social and environmental impacts?

From Table 2, a simple calculation may be done through which the production value of the industry vis-à-vis investments may be seen. Using 2015 data, for example, net productivity/income may be crudely estimated at PhP 65.27 billion(derived from gross production value less cost of investments).[1] Assuming that the MGB “cost of investment” data already include all operational costs and tax payments, then it is assumed that this income is being siphoned off by foreign investors and mining operators to their countries offshore, therefore, not really benefiting the domestic economy. As the table shows, total taxes paid to the government are estimated at PhP 29.23 billion. Is this significant? On its face value alone, one can argue that it is indeed significant.

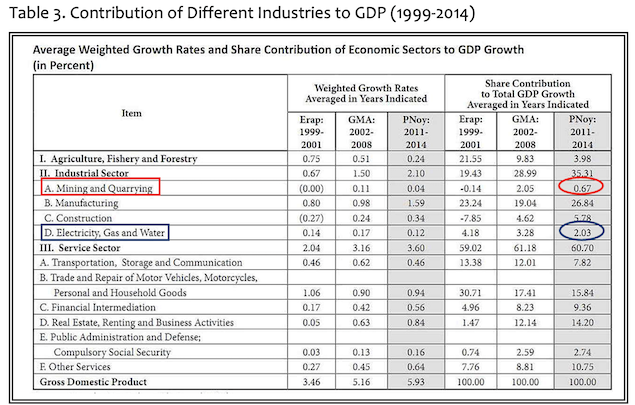

However, the same table shows that the mining industry’s contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is only at .6%!This can be appreciated in the context of how the different industries contribute to the country’s GDP. Fortunately, a study by Lim (2016) had developed a table that already summarized the data that we need (Table 3).

by this author.

As Table 3 shows, the mining industry is the lowest performer (and contributor) to the country’s GDP! Another low contributor—electricity, gas, and water sector—is contributing to the GDP at an even higher rate of 2.03%. A quick analysis, therefore, reveals that with the extent of damage that the mining industry leaves on the country’s environment, the economic benefit may not be enough to justify the accommodation and support that it is receiving vis-à-vis other sectors. Using an analogy, for example, is it still wise for a businessman with 11 employees (from the 11 sectors above) to continue hiring a miner when this employee cannot even remit a full one peso to the required 100-peso income in a day and who leaves so much destruction just to remit 67 centavos?

[1] This estimation is very simplistic as the MGB data do not give the complete picture as to how the values in the table were derived (e.g., whether the cost of investments included all costs such as employment costs and taxes, whether the cost of investments cover new investments for the current year only). Nevertheless, even with this very crude/simplistic estimate, the true value of net productivity may be close to this estimate. However, note that there may be some typographical errors in the table vis-à-vis total exports and gross production value (e.g., it is confusing why “total exports” will be higher than the gross production value).

Of course, managing a whole country is not as simple as running a business with 11 employees. However, the complexity of the mining dilemma should be appreciated not just in the economic sense but also to the over-all quest for genuine and sustainable development, which puts strong emphasis on the ability of future generations to sustain themselves as well as the social and cultural value of community life.

The next section then discusses the impacts of mining briefly, an understanding of which is necessary so as to guide all development, rehabilitation and remediation efforts.

2. The other side of the ‘fence’ – negative impacts of mining

The value of mining should be juxtaposed with its impacts, particularly that it is highly-extractive, with its impacts going beyond this generation.

Most of the negative impacts are on the environment and health. Mining activities generate significant waste dumps. Most operations expose sulfur-bearing overburden, which often leads to acid generation that may potentially contaminate soils, surface and groundwater, and negatively impact local and downstream ecosystems (Adibee, 2013). These findings had been reiterated in many studies, analyzing that the overburdens are mostly acidic in nature and with very low organic matter content, making them poor habitats for trees and plants. These overburdens are mostly very coarse or compacted, reducing their ability to retain water, contributing to poor drainage (Jha and Singh, 1992, as cited in Tripathi & Singh, 2008).

Heavy metals are products of the earth, however, “human activities opened Pandora’s box spreading these toxic metals throughout the environment” (Ashraf, 2011). A study team led by Ashraf (2011) has investigated formerly-mined sites in Bestari Jaya, Malaysia and their investigations revealed high levels of metals in the air, water, and topsoil. “High concentration of some of the heavy metals have direct effects on the growth of crops while some don’t have direct effect but may affect the animals feeding on the crops” (Ashraf, 2011). There is a dearth of journal-published studies available for Philippine-based mine sites but a study by Williams et al. (2000) revealed higher level of mercury in the hair of mine workers tested in Apokon, Mindanao. Although the exposure of the workers is “subcritical”, the researchers recommended improvement of operating procedures particularly with the storage of contaminated tailings.

The impact on air quality is also a growing concern. In a case study on a mining area in Rajasthan India, about 75 (25%) of the 300 mine workers interviewed exhibited symptoms of dust-related diseases (Sinha et al., 2000).

Meanwhile, the social impacts are very significant, too, highlighting the sensitive nature of land rights vis-à-vis our indigenous peoples (IPs) as well as over-all patrimony. A study by Hughes (2000) has succinctly expounded on the IP-land nexus, reiterating social criticisms against so-called ‘development’ projects. These projects “destroy the environment, lifestyle, identity, culture, and self-sufficiency of indigenous peoples” (Hughes, 2000).

In order to present a brief summary of the environment, health, and social impacts of mining, a list is provided here.

Mining and its negative environment, health, and social impacts

Environment

- Destroying /changing the landscape and ecosystems

- Deforestation

- Slope destabilization

- Watershed destruction

- Negatively impacting biodiversity

- Waste materials

- Erosion and sedimentation (which can affect fishery spawning)

- Siltation; siltation of irrigation canals and paddy fields

- Alteration of sea-bottom topography

- Soil and water acidification and acid mine drainage; increased water turbidity

- Water shortage and pollution/contamination

- Food insecurity, crop damage (agriculture)

- Air pollution

Health

- Water and soil contamination and air pollution leading to diseases

- Genetic impact/unknown diseases that may only appear in the next generation(s)

Social

- Displacement of indigenous peoples and upland communities

- Over-reliance on “foreign support” weakens/undermines political will and capability

- Culture of over-dependence on foreign investments (lowers national pride and identity)

Note: This list had been developed by this author with some notes/ideas adapted from Haribon Foundation and Birdlife International (2001) and IBON (2006), as cited in Bravante & Holden (2009); (Sinha et al., 2000); and Hughes (2000).

3. Policy environment

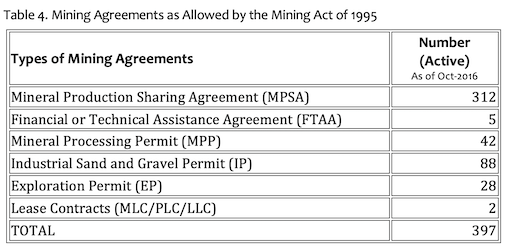

All mining activities in the country are governed through the Mining Act of 1995. This may be among the ‘culprits’ behind the wanton destruction of lands for the sake of mining. For one, the law allows 100% foreign ownership of mining companies provided that the investment is above 50 million US dollars. This is done through the Financial and Technical Assistance Agreements (FTAA), one among the six (6) mechanisms that are allowed by the law. A visit to the MGB website revealed 397 active agreements, most of them falling under Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA) (MGB, 2016a). Table 4 shows the breakdown of these agreements.

Bureau (2016a)

Fortunately, Executive Order 79 was issued by then President Benigno Aquino in 2012 (Hicks et al., 2013). It is not perfect but, at the very least, addresses some of the criticisms and challenges of the Mining Act. It also reiterated the moratorium on the issuance of new contracts, which was issued in 2011, largely because of the rising complaints against mining operations. Moreover, the mining EO enumerates five categories of areas that are “no-go zones” or those areas where mining is strictly prohibited. These include National Integrated Protected Areas, prime agricultural lands, critical ecosystems, and tourism development areas.

It should also be an indication of “better days to come” as the current administration particularly through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), has been strictly monitoring and, in fact, already suspended, mining operations. As of September 2016, the DENR has already suspended 10 firms and recommended the suspension of 20 more mining operations (Gamil & Domingo, 2016).

4. Sustainable mining

Any remediation and rehabilitation plan should be anchored on the principles of sustainable development. With climate change as another crucial dilemma, it is also necessary to incorporate the prescriptions of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

But what is sustainable mining? Is it even possible? At the onset, this author believes that such a concept is flawed in the sense that mining is about extraction of non-renewable resources—by its very nature, it can never be sustainable. Once a non-renewable resource is extracted, it is gone forever. Minerals may still “grow” somehow, but it will take a long time, perhaps millions of years. Therefore, the concept of “sustainability” as a condition that allows future generations to enjoy the same resources that we are enjoying now seems contradictory to the goal of mining: to extract minerals that are very limited.

Bravante & Holden (2009) has been vocal about their misgivings, saying that making it easy for mining companies to operate here (e.g., through easy EIA permitting) and cause “potential irreparable environmental harm that further impoverishes the weakest sectors of society” does contradict the move toward authentic development. The negative impacts of mining “make it a source of long-term poverty not prosperity” (Bravante & Holden (2009).

However, for the sake of building an argument for sustainable mining, which requires a plan for remediation, restoration, and rehabilitation, it is necessary that the concept is accepted at least in the sense that it cautions us against greed and tells us to be more responsible miners.

Hicks et al. (2013) argued that there are genuine efforts to call for the development of “natural resource policies that balance economic and energy needs with the desire to protect and preserve the environment.”

Sustainable mining should then be seen as part of attempts by countries to strike a balance between economic development and social benefits and equity while preserving the integrity of their natural endowments and ecosystems. For mining, it is in a unique position because it is harmful (destructive), yet, economies cannot exist without it. Striking a balance is indeed a challenging feat but there is a moral and societal obligation to carve a path towards more responsible and sustainable mining. Remediation and rehabilitation after closure or decommissioning of mine sites is a part of this path.

III. Toward remediation and rehabilitation

1. Remediation and rehabilitation in the context of mining

Rehabilitation in the context of mining refers to the different strategies being applied to remediate and rehabilitate (or restore) previously-mined sites. This often involves “re-establishment of vegetation communities after mining, irrespective of whether the project aims for full ecological restoration (SER 2004) or for a low- diversity vegetation cover that is safe, stable and sustainable under future land uses” (Lamb et al., 2015). It is considered crucial to environmental sustainability and often aims to regenerate natural ecosystems so that they can eventually become productive again.

There are abundant literature and research works already undertaken on rehabilitation of mined sites particularly in countries like Australia, Canada, and Australia. However, there is still a dearth of peer-reviewed or journal-published case studies and reports on Asian countries particularly the Philippines. In fact, this author came across a few articles only (non-journal published) on rehabilitation efforts in the Philippines. One of them, published by The Standard (2014) reported that there are currently thirty-one (31) mine sites that have shut down and needing rehabilitation works. Out of these 31 sites, 16 are under initial assessment and only one site—the old Bagacay Mines in Samar—is being rehabilitated (The Standard, 2014). Meanwhile, Philex Mining is currently rehabilitating its closed mine in Sipalay, Negros Occidental and Padcal Mine, in Benguet (which is now a bamboo forest (The Standard, 2014).

This is then an opportune time to ensure mining is part of the conversations especially as we tackle charter change. This will also hopefully lead to forward-looking rehabilitation framework and projects), realizing the urgency of assisting the government in rehabilitating those 31 sites.

2. Steps in rehabilitation of mined sites

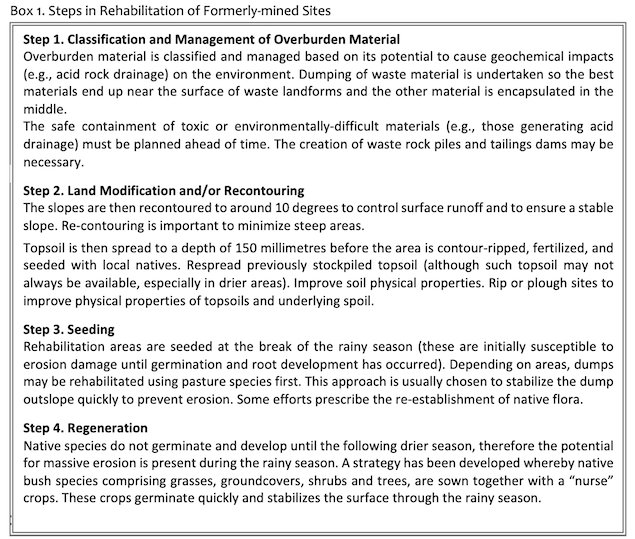

There are no absolute rules in rehabilitation although experts prescribe common steps in rehabilitating closed/decommissioned mine sites. To ensure brevity, these prescribed steps are shown in Box 1.

3. Key challenges in mine rehabilitation work

Rehabilitation works on previously-mined sites are complex undertakings that cut across many disciplines. For this fact alone, the work is long, costly, and tedious. A study by Alexandrescu et al. (2014) has analyzed the misunderstandings and “dissonance in collaborative research on brownfield regeneration” (the term often used for remediating and rehabilitating abandoned sites, which had been previously used for industrial and mining purposes) and highlighted the many factors for them. These factors include differences in “communication and cooperation skills and cultures” of project members and expectations of local stakeholders.

Alongside those challenges, there are key aspects that are also at the core of the work. For the sake of brevity, this paper will concentrate briefly on two key issues, which should be seriously considered if we are to become successful in our rehabilitation works: (i) policy and (ii) cost considerations.

4. Policy directives in the Philippines

The main bases for rehabilitation work in the Philippines are stipulated in DENR Administrative Orders 2005–07 (“Amendments to Chapter XVIII of DENR Administrative Order No. 96-40 as Amended Providing for the Establishment of a Final Mine Rehabilatation and Decommisioning Fund”) and AO 2015-02 (“Harmonization of the implementation of the Philippine environmental impact statement system and the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 in relation to mining projects”) (DENR, 2005 and 2015).

These rules require mine operators to contribute to Mine Monitoring Trust Fund and Mine Rehabilitation Fund, which, as the names connote, will be used to conduct monitoring of mine operations and pay for future rehabilitation work. Under these rules, the operators are also required to develop a Final Mine Rehabilitation/Decommissioning Plan (FMR/DP). These are certainly important regulations but there are perceived weaknesses such as the clause on the duration of responsibility. Bravante & Holden (2009), for example, had highlighted that the FMR/DP stipulated the operators’ responsibility over a 10-year period only after closure. Given that the impacts from mine operations (e.g., as acid mine drainage) cover a significantly “long geologic time scale”, this is a very short period for the obligation of operators (Bravante & Holden, 2009). They also asserted that the rulings are based on “risk-based methodologies/approaches”, which are not considered the better framework for protection as compared with, for example, a worst-case scenario approach (Bravante & Holden, 2009). The worse-case scenario approach is more appropriate given the high vulnerability of the Philippines when it comes to natural calamities (Bankoff, 1999, as cited in Bravante & Holden, 2009).

5. Massive costs of rehabilitation

It is difficult to give an estimate on how much a good rehabilitation work may require. There are industry examples but it is still difficult to contextualize them particularly that the extent of degradation and the level of impacts up to the future are also difficult to ascertain. However, if we are to use actual experiences, a study by (Holden, 2005) has shared that a rehabilitation work in a mine site in Montana, US, spent about $50 to 190 million.

Now, here is where the problem begins. The Mine Monitoring Trust Fund requires a minimum of PhP 150,000 while the Mine Rehabilitation Fund requires a maximum of 5 million pesos only (DENR and Bravante & Holden, 2009). Compare $50 million to 5 million pesos and you are definitely going to shake your head in disbelief!

There are certainly many ways to address the costs of rehabilitation works but the first thing that the country should do is reviewing and amending the policies sooner than later. This is a perfect time to go through this process given the strong imperative to recover from the impact of Covid-19. A framework for both development and rehabilitation should also be customized based on local conditions.

IV. Moving forward

It is hoped that this article leads to further conversations toward wiser and more sustainable develop and use of our mineral resources.

Mining indeed hurts our health and environment as well as our national and community pride. The cost is so huge and encompasses a long temporal scope that one begins to wonder whether rehabilitation work is even worth it.

However, as environmental managers, we also appreciate that we are expected to support our government and country in developing realistic, efficient, and effective solutions with how we can optimize the use of our resources given our economic requirements.

Lessons from other countries must also feed into the development and rehabilitation plans for Philippine mine sites—with each option undergoing a cost-benefit analysis at the minimum. For example, while re-vegetation and reforestation are certainly based on best practices in other countries, there may be other strategies that may be adopted, particularly if the provinces that are hosting those closed/decommissioned sites have special features, which might necessitate more innovative thinking and strategies.

Sustainable development considers the future generations. It is a participative process where everyone is part of the decision-making journey. As Broad and Cavanagh (1993) wrote, “the struggle for the environment, and for control of resources, requires a far more participatory notion of development” (as cited in Alexandrescu et al., 2014). Most of all, stakeholders should see the importance of claiming their sovereign rights over their own resources. This is enshrined in the Philippine Constitution. It is indeed timely that the charter is reviewed and revised—including its economic provisions. However, there are critical industries and sectors that must still be protected—and mining is one of them.

Indeed, the time is ripe for the Philippines to “mine” its own business.

When we look around us, we see mining as an intricate part of our existence—we are challenged to create a world where mining will truly be pro-Filipino and sustainable, at least to the extent possible.

We owe this existence for the greatest love and union that happened many years ago, a pledge that was sealed with a ring (product of mining). Now, therefore, we are called upon to let that love inspire us as we create a better and more sustainable country for the Filipinos, for you and me, and for our children’s children.

We owe this existence for the greatest love and union that happened many years ago, a pledge that was sealed with a ring (product of mining).

Now, therefore, we are called upon to let that love inspire us as we create a better and more sustainable country for the Filipinos, for you and me, and for our children’s children.

Mama Earth loves you: To maintain independence, this website is self-funded and this write-up is not a commissioned work. There is no request for donation but if you can plant a tree (or two!) on your birthdays, it will really be awesome and will make Mama Earth very happy! P.s. It’s better if you could join the You’ve Got TREE-mail! Chain.

REFERENCES

Note: Some of the references here don’t appear in this article anymore as this is a shorter version of the paper that I had developed for my master’s course work. I am sharing them in full so as to help future researchers and scholars.

Adibee, N., Osanloo, M., & Rahmanpour, M. (2013, October). Adverse effects of coal mine waste dumps on the environment and their management. Environmental Earth Sciences, 70(4), 1581-1592. doi:10.1007/s12665-013-2243-0

Alexandrescu, F., Bleicher, A., & Weiss, V.D. (2014, December). Transdisciplinarity in Practice: The Emergence and Resolution of Dissonances in Collaborative Research on Brownfield Regeneration. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 39(4), 307-322. doi: 10.1179/0308018814Z.00000000094

Ashraf, M. A., Maah, Mohd, J., Yusoff, I. (2011). Analysis of Physio-chemical Parameters and Distribution of Heavy Metals in Soil and Water of Ex-Mining Area of Bestari Jaya, Peninsular Malaysia. Asian Journal of Chemistry, 23(8), 3493-3499. Retrieved from 1513249762/fulltextPDF/C6186424897A4C05PQ/93?accountid=47253

Bravante, M. A. & Holden, W. N. (2009, September). Going through the motions: The environmental impact assessment of nonferrous metals mining projects in the Philippines. Pacific Review, 22(4), p523-547. doi:10.1080/09512740903128034

Department of Environment and Natural Resources. (2005). DENR Administrative Order 2005-07, Amendments to Chapter XVIII of DENR Administrative Order No. 96-40 as Amended Providing for the Establishment of a Final Mine Rehabilatation and Decommisioning Fund. Retrieved from http://policy.denr.gov.ph/2005/dao/dao2005-07.pdf

Department of Environment and Natural Resources. (2015). DENR Administrative Order 2015-02, Harmonization of the Implementation of the Philippine Environmental Impact Statement System and the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 in Relation to Mining Projects. Retrieved from http://server2.denr.gov.ph/uploads/rmdd/dao-2015-02.pdf

Domingo, J. P.T. & David, C.P.C. (2014, July-December). Geochemical Characterization of Copper Tailings after Legume Revegetation. Science Diliman, 26(2), 61-71. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=24&sid=4627d57c-4bea-4cd7-b8f4-184962f6ad42%40sessionmgr4006&hid=4214

Dybowska, A., Farago, M., Valsami-Jones, E., & Thornton, I. (2006, May): Remediation strategies for historical mining and smelting sites.Science Progress, 89(2), 71. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1244894480/fulltextPDF/C6186424897A4C05PQ/96?accountid=47253

Gamil, J.T. & Domingo, R.W.(2016, September).20 mining firms face suspension. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Online). Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/819728/20-mining-firms-face-suspension

Griffin Coal. (2016). Coal Production Method Step 5 Rehabilitation. Retrieved from http://www.griffincoal.com.au/coal-production-method/rehabilitation/

Hicks, R. M., Acosta, N.,& Candelaria, S.M. (2013). Crafting a sustainable mining policy in the Philippines. Natural Resources & Environment, 27(3), 43.Retrieved from go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=ITOF&sw=w&u=phup&v=2.1&id=GALE%7CA365691119&it=r&asid=7a89c10036028a55c8ee18838fa827d3

Holden, W. N. (2005, September). Civil Society Opposition to Nonferrous Metals Mining in the Philippines. Voluntas, 16(3), 223-249.doi:10.1007/s11266-005-7723-1

Holl, Karen D. (2002, December). Long-term vegetation recovery on reclaimed coal surface mines in the eastern USA. Journal of Applied Ecology, 39(6), 960-970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00767.x

Hughes, M. L. (2000). Indigenous rights in the Philippines: Exploring the intersection of cultural identity, environment, and development. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review, 13(1), 3-21. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/225516778/fulltextPDF/BE48ADA088094D7BPQ/5?accountid=47253

Inman, M. (2011, December 21). Planting Wind Energy on Farms May Help Crops, Say Researchers. National Geographic News. Retrieved from

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2011/12/111219-wind-turbines-help-crops-on-farms/

Lamb, D., Erskine, P. D., & Fletcher, A. (2015, September). Widening gap between expectations and practice in Australian minesite rehabilitation. Ecological Management & Restoration, 16(3), 186-195. doi:10.1111/emr.12179

Lim, J.A. (2016, March). Economic Performance of the Administration of Benigno S. Aquino III. Action for Economic Reforms – Industrial Policy Team. Retrieved from http://aer.ph/industrialpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Assessment-of-Econonomic-Performance-of-Aquino-2016.pdf

Makineci, E., Gungor, B. S., & Kumbasli, M. (2011, April 18). Natural plant revegetation on reclaimed coal mine landscapes in Agacli-Istanbul. African Journal of Biotechnology, 10(16) 3248-3259. doi:10.5897/AJB10.2499

Meier, P. H. (2011, June 10). Wind Farms Adapt to Forest Conditions – New generations of turbines with higher towers and longer blades are opening up previously impractical sites to development. TUV SUD Industrie Service. Retrieved from http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/articles/print/special-supplement-wind-technology/volume-1/issue-3/wind-power/wind-farms-adapt-to-forest-conditions.html

Mines and Geosciences Bureau. (2016a). Approved mining permits and contracts. Retrieved from http://mgb.gov.ph/2015-05-13-01-44-56/2015-05-13-01-46-18/2015-06-03-03-42-49

Mines and Geosciences Bureau. (n.d.). Metallic ores and industrial minerals of the Philippines Retrieved from http://mgb.gov.ph/images/links-images/MetallicOresAndIndustrialMineralsOfThePhilippines.pdf

Mines and Geosciences Bureau. (2016c). Mining industry statistics. Retrieved from http://mgb.gov.ph/attachments/article/162/MIS(2015)%20(1)%20(1).pdf

Official Gazette (2016, February 29). Citizen’s guide to the 2016 budget now online.Retrieved from http://www.gov.ph/2016/02/29/citizens-guide-2016-budget/

PacifiCorp. (2011). Glenrock Wind Project. Retrieved from http://www.pacificorp.com/content/dam/pacificorp/doc/Energy_Sources/EnergyGeneration_FactSheets/RMP_GFS_Glenrock.pdf

Sinha, Rajiv K; Pandey, Dhirendra K; Sinha, Ambuj K. (2000, September). Mining and the environment: A case study from Bijolia quarrying site in Rajasthan, India. Environmentalist, 20(3), 195-203. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/221749229/fulltextPDF/C6186424897A4C05PQ/34?accountid=47253

The Standard. (2014, April 2-3). Reviving abandoned mines. Retrieved from http://www.thestandard.com.ph/news/-provinces/144260/reviving-abandoned-mines.html

Tripathi, N., Singh, R. S.(2008, November). Ecological restoration of mined-out areas of dry tropical environment, India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment,146(1-3), 325-37. doi:10.1007/s 10661-007-0083-7

Visaya-Ceniza, R. A.(2015).Dig to Live: An Investigation of the Psychological Well-Being of Women Miners in Davao Oriental, Southeastern Philippines. The Professional Counselor,5(1), 91-99. doi:10.15241/rav.5.1.91

Whiting, S. N.; D. Reeves, R.; Richards, D.; Johnson, M. S.; Cooke, J. A.; Malaisse, F.,… Baker, A. J. M. (2004). Research priorities for conservation of metallophyte biodiversity and their potential for restoration and site remediation. Restoration Ecology, 12(1), 106-116. doi:10.1111/j.1061-2971.2004.00367

Williams, T. M., Apostol, A. N., Jr., & Miranda, C R.(2000, March). Assessment by hair analysis of mercury exposure among mining impacted communities of Mindanao and Palawan, the Philippines.Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 22(1), 19-31. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/741704673/fulltextPDF/8AEB62CD6A564D30PQ/26?accountid=47253