When the spirit meets the law: Innovation in law pedagogy (and why it’s the key to a high-integrity future)

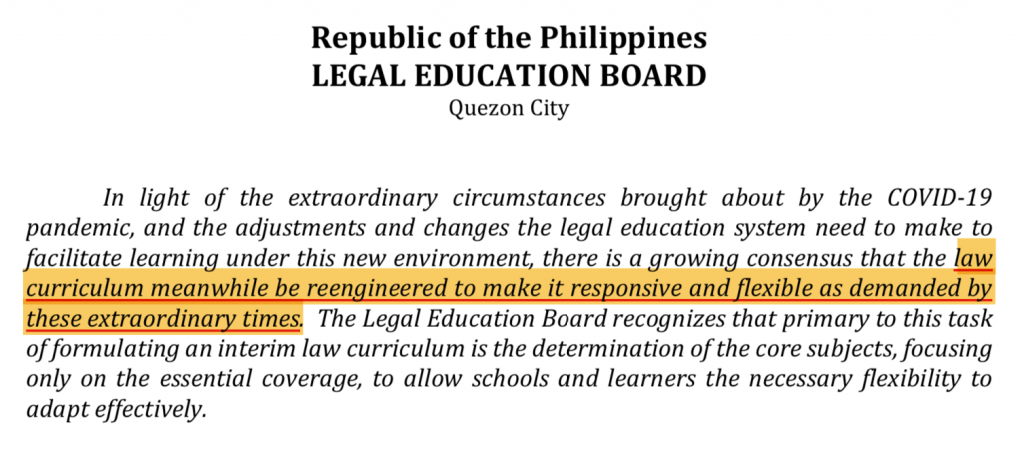

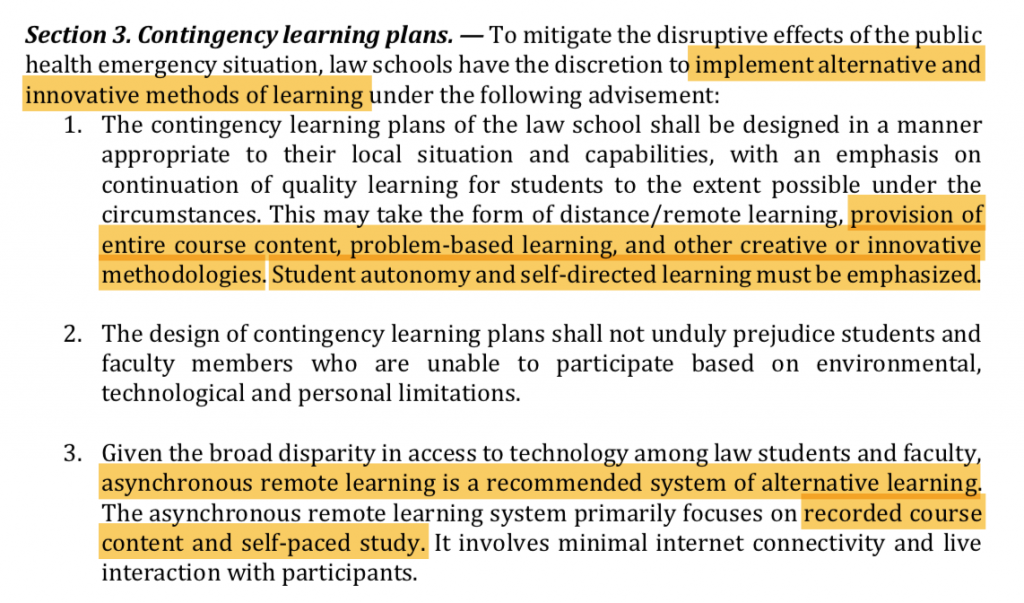

Kudos to the Legal Education Board (LEB)! It is definitely the perfect time to “re-engineer” the law pedagogy. To share the gist of what it has been issuing recently, here are a few screenshots:

Fortunately, such re-engineering is already being done all over the world (and not just because of the new normal). Law /Juris Doctor students certainly hope that the emerging pedagogy and culture will soon be embraced by law schools here in the Philippines. (Patience is a virtue indeed!)

Thank you, LEB! It is actually tough to advocate for innovation and reforms because our schools (and some educators) are still highly traditional. Patience is a must if you want to join the transformation process because advocates or changemakers are often met with either indifference/inertia–after all, change brings people out of their comfort zones–or downright hostility or censure (more on this later).

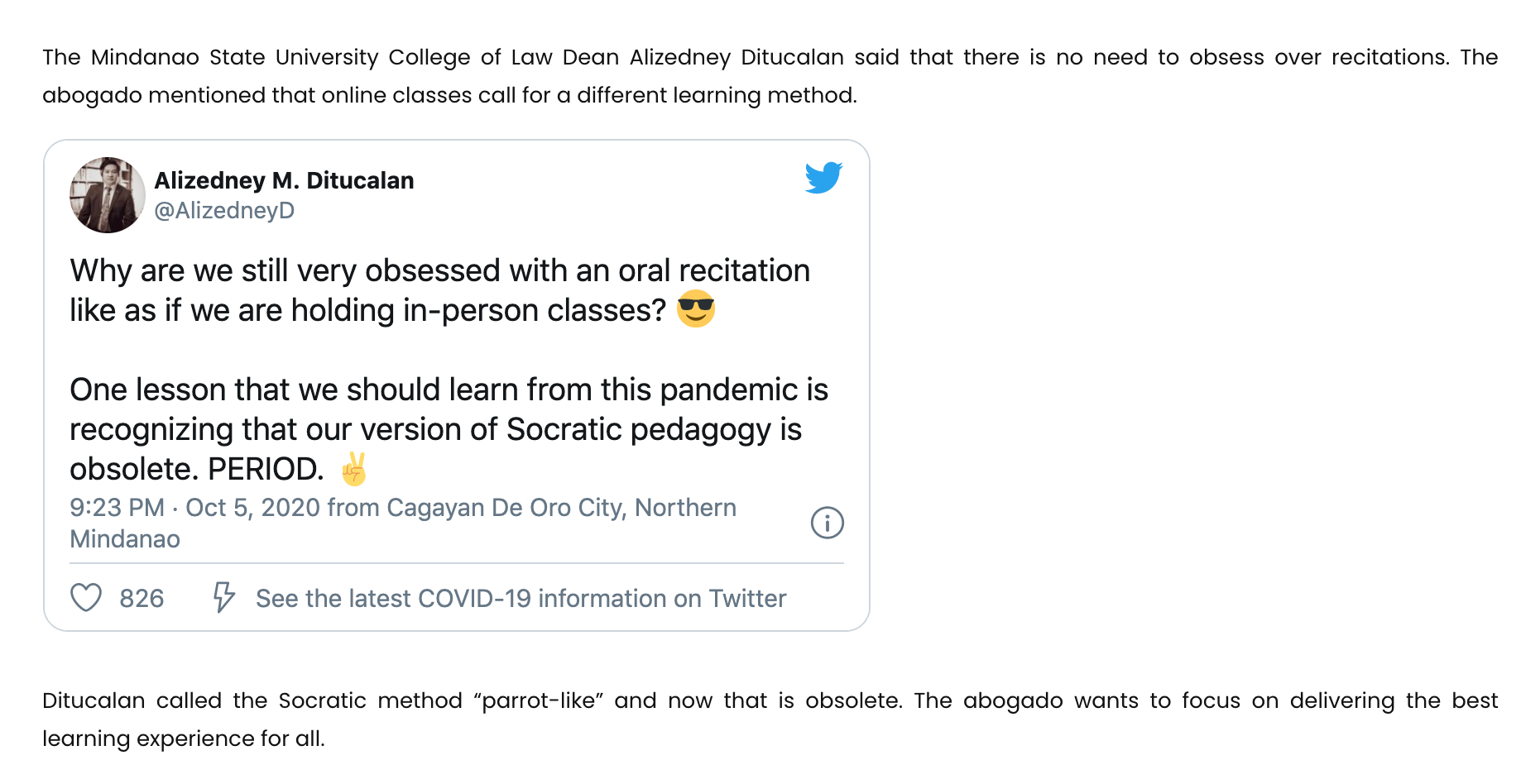

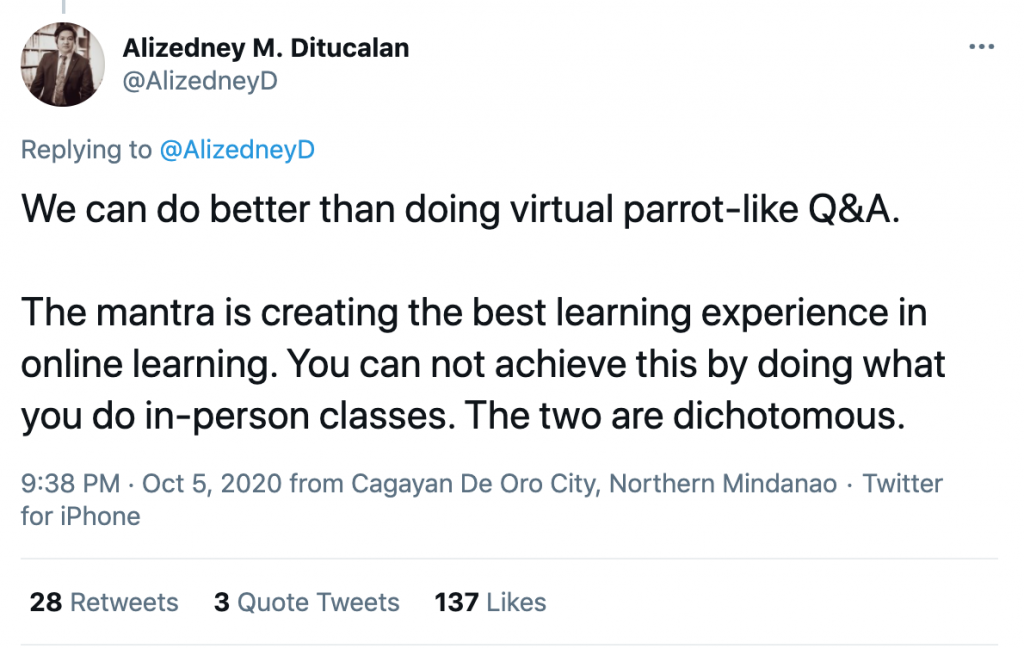

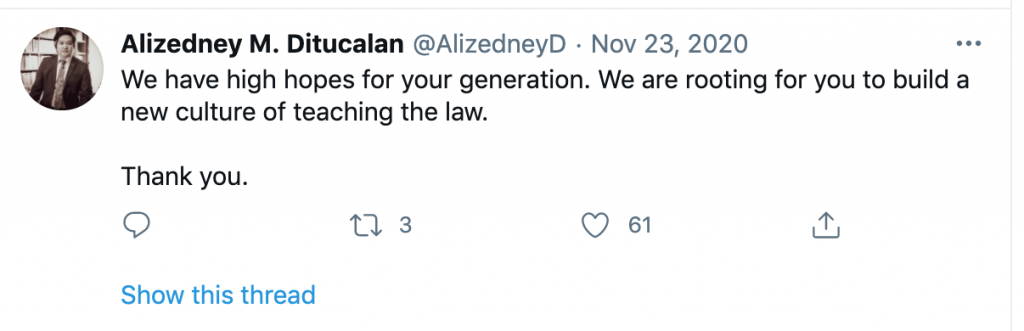

However, there is hope and champions are now making their voices heard. One of them is Atty. Alizedney Ditucalan, the Dean of Law School of the Mindanao State University, who has posted these in his Twitter (one of them covered by Abogado.com.ph), “One lesson that we should learn from this pandemic is recognizing that our version of Socratic pedagogy is obsolete. PERIOD” (emphasis mine). The screen caps of his Tweets are shared below.

Source: Dean A. Ditucalan, via Abogado.com.ph and Twitter.

Why the need for a change in pedagogy and culture? The answers are more complex than an enumeration but let me be brief in discussing the rationale. (Be forewarned though: This post is a long read so I suggest to read this in 2-3 chunks of time.)

1. Changing needs and circumstances including the challenges of the new normal require a serious shift—let’s face it, the new normal is difficult enough; however, because of technology, education is evolving and getting more exciting. In fact, with all the tools available now, it can even be made better. (The economic systems just need further improvements so as to address the digital divide.) Indeed, “the old” needs to embrace “the new”. New technologies and emerging ones are simply going to run us over if we do not re-engineer and re-calibrate.

The change should also be accompanied with a more inclusive and collaborative culture. The change will not happen with a faculty that still refuses to look at the big picture and embrace the call for change. Collaboration is the new normal. (More on this in No. 5 below.)

2. Clogged courts – this is a complex issue that deserves its own article but suffice to say, our literature is also replete with insightful articles on this—the Philippines’ justice system seriously needs reform. It is a common knowledge that court cases take several years, with some reaching beyond 15 years, especially if they reach the Supreme Court. Nevertheless, steps are being done and among them is the practice of barangay-based justice system. Kudos to all who pushed for these early initiatives! However, changes should also begin right where it all begins: inside law schools.

There are several reasons for this and among them is the indiscriminate filing of court cases (Castro as cited in Tadiar, 1999). According to Tadiar (1999),

“The hypothesis of Chief Justice Castro is that litigation prone lawyers have the courts [as] the place of initial settlement rather than the ultimate place of dispute resolution that they were originally meant to be. The solution to this cause must start with the law curriculum to give more emphasis to the “preventive lawyering function” in order to balance the heavy concentration of preparation for litigation. A re-orientation of lawyers along this line seems wanting.”

Tadiar, 1999

The law curriculum and culture are simply too biased toward adversary and litigation. This has to change. Lawyers, should first and foremost, be agents of resolution, peace, and reconciliation.

3. Corruption – lawyers are not ‘super’ beings who could make corruption disappear through a magic wand but they have a big role to play toward the creation of a high-integrity future. Corruption does not only happen in the government sector. In fact, based on what I have seen—it is either more rampant in the private sector or it is largely unchecked there that it appears “bigger”. Lawyers (as part of the justice system) have a big role to play. They cannot be the first ones circumventing the law. Atty. Lorna Patajo-Kapunan (2017) has highlighted the important role of law schools in ensuring upright lawyers:

“Perhaps the solution to deceit, malpractice, gross immoral conduct and moral turpitude of lawyers is not disbarment or suspension, but a close monitoring and supervision of law schools to ensure that they are infusing in their law students the importance, nobility and dignity of the legal profession so that when these law students are admitted to the Bar, they subscribe in solemn agreement to dedicate themselves to the pursuit of justice and swear to become guardians of truth and the rule of law, as well as instruments in the fair and impartial dispensation of justice.” – Kapunan, 2017

(Emphasis mine)

(Closer to home, this is the motivation behind Integrity Institute, one of the core initiatives of Anna’s Trees & Innovations. For a quick read, please go here.)

4. Low success rate in bar exams– as a coach and educator, too, I am not really a believer in the current system of “exams” but in the absence of an alternative professional licensing scheme, the bar plays a role. Unfortunately, only about ¼ of our bar takers pass the exam. While there are provisions for re-taking, the success rate is still quite low: only 27.36% passed it in 2019 while 22.07% passed it in 2018.

We are tempted to ask, are the schools and their pedagogy not preparing the students well? Are the questions not “fitted” for the type of learning that students went through? Or better yet, is the bar exam the perfect tool for measuring the preparedness of a law practitioner? These questions should drive some of the changes and innovations, too.

For an idea on the bar passing rate from 1995 to 2015, please go to this link:

For an idea of how a country without a bar exam does the law practitioners’ qualification (e.g., Australia), please go to this link.

The bar exam itself needs a revisit but I will focus on this a future post. In the meantime, the work, A Better Bar: Why and How the Existing Bar Exam Should Change is highly recommended (Curcio, 2002). A passage is shared below:

“…a blue-ribbon commission of lawyers, judges, and law professors conducted an in-depth study and concluded that competent lawyers must also be able to do legal research, conduct factual investigations, problem solve, communicate effectively, counsel clients, negotiate, organize and manage legal work, recognize and resolve ethical dilemmas,and, in some instances, litigate and effectively use alternative dispute resolution procedures.

Most of these skills, however, are not tested on the bar exam, are only cursorily assessed during law school, and are not factored into the law school admissions process. Further, qualities like a demonstrated commitment to promote social justice, a sense of fairness and morality, and the willingness to perform public service activities, although given lip service, are not accounted for in any meaningful way in the process of deciding who may get a law license.”

Curcio, 2002

(Emphasis mine; some sentences had been attributed to other authors so please refer to the original work)

5. Non-collaborative and adversarial culture leads to poor mental wellness (and such culture does not lead to better lawyers) –before learners could become good lawyers, they first need to become good human beings. However, because of the seemingly unhealthy and non-collaborative culture (a one-way mentality where learners are not treated as co-equals but as “mere students” therefore, “lower in hierarchy” instead of two-way “collaborators”) in many law schools, it’s easy to understand why it becomes easy for law schools to churn out lawyers who eventually end up growing inflated egos or superiority complex.

A great work, “Law School Culture and the Lost Art of Collaboration: Why Don’t Law Professors Play Well with Others” (Meyerson, 2015) closed in on the seemingly poor collaborative culture in law schools and why this must be changed.

“The values we attend to in the classroom are apt to be individualism and autonomy, which we present as the basis for the adversary system…Those values have led to what Professors Sturm and Guinier term law school’s “culture of competition and conformity.” To the extent that law professors avoid collaboration, so will their students…

Meyerson, 2015

…what is required is a recognition of the numerous benefits that derive from working together and the subsequent need for responsible legal educators to prepare our students for a collaborative legal field. It would also help to realize that collaboration does not mean the demise of individual effort, individual responsibility, or individual rewards…When properly understood, collaboration is not the opposite of individualism, but a vital part of the process whereby an individual can achieve more of his or her unique potential.”

(Emphasis, mine)

Everyone can relate to this implied messaging in traditional set-ups–“estudyante ka lang, ako ang teacher kaya matakot ka sa akin, pwede kitang ibagsak,” (You’re just a student, I am the teacher, be scared of me, I can flunk you.) This messaging (as a sub-culture) is a no-no. A lawyer-professor recently addressed a student in an email and began the email with “To Student – [insert full name]”. Was that intentional? We don’t know. However, whether intentional or not, this needs attention.

How do we address a student in a more respectful and inclusive way–considering him as a co-equal in the academe and community? For one, law students are mostly adults already. Secondly, we can try removing the label “student” and simply use, “Mr.” or “Ms.” or whatever the appropriate title should be. In fact, the first name or the family name can suffice. Students respect their professors with titles such as “Prof” or “Atty”–the least that students expect is treatment as co-equals (as human beings). Meador (2019) recommended some basic rules:

“We expect our students to be respectful to us and we should, in turn, be respectful to them at all times. This isn’t always easy, but you must always handle interactions with students in a positive manner…The key is to talk to them, not down to them…never misuse your authority.”

Meador, 2019

(Emphasis, mine)

That “talking down” is highlighted. It’s a subtle condescending behavior. Respectful and culturally-appropriate disciplining helps in the primary, high school, and even college levels. However, in graduate and law schools–this looks archaic and non-inclusive–ultimately signaling that it’s ok to treat others in the same way.

Adult and graduate learners are mostly working already, many with 10+ or even 20+ years of professional experience. They have something to offer, too, on the table. However, this inertia (or downright refusal?) to engage them is like wasting precious resources. The current law education system certainly produces well-adjusted, upright, and high-integrity lawyers, however, there are also, sadly, rotten tomatoes in the basket. (And this is true in all other professions, to be fair. However, we must recognize that lawyers–by the very nature of the profession–are expected to to be the first ones to show good examples, in the same way that doctors are expected to practice and inspire us toward healthier lifestyle.)

Classrooms must allow healthy discussions among peers (both between faculty and learners and among learners themselves). It’s definitely alright to argue about different opinions but it’s definitely not ok to censure one’s fellow student inside the classroom.

Corollary to this is to ensure that professors, as mentors, are always inspired to protect idealism, equality, and integrity. The call for transformation should not become like a heavy baggage to carry–learners should always feel safe to talk about it. When one’s classroom (virtual or otherwise) suddenly feels unsafe for one’s world views, the quality of education suffers. Intellectual debate is ok; censorship is not.

An article by K. Smith (2020) resonates with this example of classroom hierarchy and inequality not just between teachers and students but between/among students themselves (because, somehow, students begin embodying/imbibing the culture that they are exposed to as highlighted by Meyerson as well). In the article, Disrupting patriarchy in the classroom with Carol Gilligan, focus in education as a whole and alerted educators about the danger of perpetuating inequality inside the classroom.

It’s time that law schools stop churning out future lawyers who will think of themselves as “higher beings”. The title of “Attorney” is not a free pass for arrogance. To quote a material from Gilligan (as cited in Smith, 2020):

“Imagine a young person who is celebrated for becoming valedictorian, but who manages to do so by bullying her classmates and restricting their access to study materials. In our present society, such domineering behavior is often rewarded, whether it is shown in the classroom or the board room. In a challenge to attitudes that regard such behavior as hallmarks of personal independence and maturity, Gilligan argues that this “separation of reason from emotion” is actually a “sign of injury or trauma.” (Emphasis mine)

Gilligan as cited in Smith (2020)

This was, unfortunately, playing as well in the supposedly “more mature” law classroom. The core point here is that we need brilliant lawyers but more than that, we need respectful and credible ones who will value diversity of opinion and inclusion in the middle of emerging changes. How could we fight for justice, freedom, and equality when we allow the law classroom to be breeding ground for censorship and diminishing of innovative ideas?

Here’s an article that delves into this complex behavioral problem, Why are there so many asshole lawyers? (Alvey, 2014).

Outside, the world is changing every minute. But inside some of the law classrooms, one will feel a little too trapped in another era…perhaps closer to the Stone Age? (Or is the analogy even fair? During the Stone Age, we know that human beings still care about the welfare of others. There was still a sense of community, no matter how little the food may be.)

Are our law schools rearing the future monsters and bullies in court rooms, board rooms, government offices, halls of Congress, and in real life? Instead of wise, compassionate, and respectful human beings who would first be advocates of peace, negotiations, law and order, and peaceful resolutions? Certainly, lawyers need to be brave. However, having courage is definitely not equal to being bullies. At the heart of courage is the ability to discern every thought, word, or deed–and to defend the truth without resorting to ad hominem.

Wooley (2016), in her article, The problem of judicial arrogance, underlined the need for humility in the practice of law and in the judiciary. She began her post from important insights in Life Sentence, a book by C. Blatchford (2016). I am sharing some parts here but do read her post in full soon:

“She also suggests that actors in the legal system are complicit in judicial arrogance while simultaneously having considerable arrogance of their own: lawyers and judges alike deny the rationality and dignity of the “non-lawyer,” refuse to admit their own faults, and tend both to aggrandize official power and to subdue public criticism.

I wish I could disagree with Ms. Blatchford. But I can’t. I have to reluctantly concede the uncomfortable truth of her fundamental allegation: we undermine our legal system through our own arrogance, and particularly in how we create, encourage and reinforce judicial power, unaccountability and – at the end of the day – judicial conduct that can be fairly described as arrogant.

But I do want to say unequivocally that judicial arrogance is wrong. It is a wrong that gets committed too often and called out too little. Judges* need to strive for humility – to recognize it as a virtue. Judges may be independent, but their independence exists to deliver justice to the public, not to give judges a public forum to say what they want, when they want, to whom they want. It requires, in short, humility.”

Wooley, 2016

(Emphasis, mine) *May we add, “and lawyers alike”?

This is an area that needs urgent attention and, thankfully, law schools abroad are now giving this much attention. It’s just a matter of time when Philippine schools catch up, too. (LEB is certainly in the right direction.)

Spirituality, yoga, and mindfulness in law school? Why not? A survey by the American Bar Association showed that the law profession has high rates of mental health problems and substance abuse issues among practitioners in comparison to other professions. Literature is also replete with similar findings when it comes to law schools. One of them tackled this at length in the article, Where Are We on the Path to Law Student Well-Being?

The answer is clear: law schools have a lot to do when it comes to improving mental health and consequently, the success of future lawyers. For the sake of brevity, let me quote an article directly by S.J. Quinney College of Law (University of Utah):

“The beginning of the 2019-2020 academic year introduced a new series of well-being objectives at the College of Law designed to make the experience happier, easier and more balanced for students immersed in learning the rules of law. The initiatives encompass a broad spectrum of opportunities aimed at helping students connect with self-care measures that may help them become more successful students…The law can be a uniquely adversarial, isolating, and high-pressure career. We seek to provide our law students with resources and support to navigate this path in the most healthy and resilient way possible..” (Emphasis mine)

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah

(Link is shared below)

The Law School of the University of Iowa has also underlined this:

“Law school has a reputation as an environment designed to wreak havoc on your mental health. For many people, there is the persistent imposter syndrome, the never-ending to-do list, the constant undercurrents of a rat race, and a curve that hangs like a guillotine; more importantly, the pressures of law school do not relent when life outside of Boyd takes an unexpected turn. If anything, the environment can exacerbate our struggles and further promote inequality. (Emphasis mine)

College of Law, University of Iowa

“As a community, we have a duty to demand access to adequate mental health services, to treat our peers with compassion, and ultimately, to foster a supportive culture at our law school. I want that for all of JCL, and I want that for you, too. There is nothing more important than your own health and well-being, and we must all resist the bait to think otherwise.” (Emphasis mine)

Stacey Murray, JCL Editor-in-Chief

(Link is shared below)

Meanwhile, our very own Atty. Lorna Patajo-Kapunan also advocated for the adoption of “happiness curriculum” in the education system. Her piece did not actually focus on the law school per se but in the educational system as a whole. Still, her article is a compelling read.

Does Socratic method really work? Or is this becoming obsolete under the shifting world including the challenges of the new normal?

The teaching methodology is waiting for a serious shift. For one, the Socratic method could no longer be useful nor appropriate. For example, while some professors still appreciate the value of “cold-calling” and Socratic method, it may not be generating or leading to the kind of experience that the students need (especially under the new normal). As what Atty. Ditucalan said, it’s becoming obsolete.

A professor once said in class, “students tend to ‘just read’ the cases onscreen…” (not the exact wording). Does this signal the need for a shift in mindset from the point of view of learners (who are also paying customers)? This is probably because students are pressured to read 15 to even 20 cases per class rather than concentrate on one or two at a time (at least for the purpose of active class engagement)—a load that will typically be realistic enough while still deepening comprehension and analytical skills.

Is this among the reasons why 75% of bar takers flunk the exam? Because these students spent so much of their time memorizing the laws, sweating it out and rehearsing for the Socratic cold-calls–thereby forgetting that in real life, lawyers prepare for cases weeks/months before actual litigation? Real life lawyering requires preparation, analysis, research, and case writing, and definitely not memorization? That one cannot “speak with confidence” and “from the heart and soul” if there is not much preparation for rigorous analytical skills and critical thinking (which cannot be developed while sweating it out trying to rehearse for the Socratic cold calls). As Einstein once said, “Education is not the learning of facts, but the training of the mind to think.”

Are we still wondering why 75% flunk the bar exam and many of those successful ones are being disbarred? Change is necessary and technology is a perfect tool. Sadly, when advocates try to knock on doors, respectfully offering collaboration, they could face any or all of the following reactions: (1) the cold shoulder treatment (don’t expect any reply to your letter-proposal); (2) tyrannical and hierarchical messaging (you are just the lowly student, know your place); (3) censure; and (4) downright disdain. Pasley (2016) correctly highlighted this by saying that,

Pasley (2016)

“Students who choose to speak out and challenge the unjust nature of the legal system or the social effects of law are often silenced by the professor— who will tell them they need to learn the law as it exists—and by other students*—who complain that the time spent discussing these issues will distract from material on which they will be tested.”

*This is happening in law schools (anecdotal evidence, personal communications)

However, these are not reasons for giving up. A serious shift in pedagogy and culture is definitely needed and such a shift needs time, patience, diligence, and collaboration. If one is met by arrogance and censure, give them kindness and then move on. There is certainty that they will wake up, too, eventually.

The first small steps are critical. In the example of learners who appear to be “reading from her PC’s screen,” educators need to consider that such learners are simply optimizing their tools because, now, learning is online anyway. If learners prefer to read their notes on their PCs, it is likely that they could better explain their thoughts later because computers are now the learning tools. Technology must be used to its advantage. Many people say, Google made people lazy. That’s likely a fallacy. Google made people more efficient. Now, they can learn more in lesser time. In the context of law school, learners have more time to do deep research about real-life applications and related cases.

It’s understandable that new cohorts of law students and even educators (as seen in Dean A. Ditucalan’s tweets), crave for a new ‘culture’ in law school and wish to be heard, too. In the case of forward-thinking learners, there is inefficiency in being suspended in the air (wondering about getting cold-called), dealing with the pressure to “perform”, which becomes an “obligation” rather than a beautiful experience out of genuine search for true learning and mastery of the law.

Clearly, students participate more because they are free to share insights and ask questions without the pressure of trying to understand a long list of cases (all at once), stretching their “waking hours” (sacrificing sleep and wellness), and then, sadly, spending the whole 3-hour class not really listening anymore (because they are busy “rehearsing”).

It’s not fair to educators, too. Educators should enjoy the class, too. The class easily becomes more enjoyable if the learning experience is truly authentic, two-way, inclusive, and not lost in an awkward silence because 75% of the class is simply anticipating and “rehearsing.” That had been observed in a paper by Pasley (2016) where he shared,

Pasley (2016)

“The Socratic method also produces classroom situations in which students ignore the insights of other students, instead waiting for the professor to point out the “correct” answers. Furthermore, trying to answer Socratic questions tends to make people feel like failures, as if they are being judged by the class. While this method can give students practice thinking on their feet and with public speaking, it can take time away from actually teaching the material.“

(Emphasis, mine)

The Socratic method was never proven to be the best type of pedagogy for law education and, in fact, it’s no longer used in many law schools all over the world. West (2011), for one, has succinctly explained an important point:

“Contemporary law professors aim to in still in students not only respect for the law, but also critical acuity, and it is for that reason that Socratic teaching in law schools has fallen into disuse. Socratic teaching is not designed to do that, although a healthy spirited dialogue in the classroom, most assuredly is.”

West, 2011

(Links are shared at the end of this post.)

Meanwhile, Atty. Stephen Bainbridge, a professor of UCLA School of Law, in a speech, shared,

Bainbridge, 2009

“Once I went through the twelve-step program and became what Brian Leiter calls a “recovering Socratic teacher,”[1] I noticed that I had some interesting company. Leiter, for example, has written that: “[T]here is no evidence—as in ‘none’—that the Socratic Method is an effective teaching tool. And there is much evidence that it’s a recipe for total confusion.”[2] (citations are in the Bainbridge speech)

Learners, therefore, trust that their law teachers are open to ideas. They trust that their schools and faculty also believe the learning experience is truly uplifting in many cases if they are being given the chance to flourish and find their rhythm. To apply the teachings of positive psychology–an area that considers human relationships and dynamics, which are central to law and their applications–individuals find fulfilment and happiness they can “apply their unique strengths, and develop their virtues toward an end bigger than themselves”.[3]

It then follows that this is about adapting a pedagogy that will allow mutual respect, two-way listening, and shared learning—a place where there is lesser pressure to “perform” but more more opportunities to discover more about how laws could help create a better and more just world.

Moreover, this is about 4 to 5 years

of law learners’ lives. As educators will also appreciate, law students are not

little children anymore. They are all mature, responsible professionals,

leading different lives. They are also partners and aspire for the chance and

space to co-shape /co-create their learning experience. As Bergman, said,

“Some feel that “the technique makes the teacher,” but, actually, the most effective teaching ‘technique’ is a good interpersonal relationship with one’s students.2 This means that teaching is essentially an interpersonal interaction which enables students to interact effectively with the teacher. It also helps in effectively conveying concepts, ideas and facts to students.”

Bergman, 1980, as cited in Bajpai & Kapoor, 2018

Litigation is not the end-all-be-all

Law students need to learn litigation (in culturally appropriate ways) but not all of them would like to focus in litigation. Some would like to concentrate in policymaking, corporate law, teaching, civil service, and other career pathways.

Fortunately, many educators agree that law education must be an enjoyable learning experience where learners are mentored according to their unique potential, background, and plans, and truly see them in their totality (and not not only as mere “students” or the square pegs for round holes). Many law students will become future policymakers, litigators, judges, CEOs, and trailblazers. They should be seen in the context of how much positive change can they contribute to the society later on.

Innovations and re-engineering—the way forward

The following techniques and innovations are then proposed, which will, hopefully, be adapted by Philippine law schools, following the issuances of LEB and the advocacy of other law educators such as MSU’s Dean Ditucalan:

1. Adaption of innovative methodologies. As shared earlier, many law schools are now gearing away from the Socrates method. For example, lecturers now use a combination of lectures (including those uploaded in videos),[4] group work, article reviews, policy review and formulation (including review of House Bills or Senate Bills), policy development, case studies, games and “quiz bee” shows, discussion of current affairs (with focus on laws), even film/book critiquing, etc.—all within the mutually-supportive and culturally-appropriate environment of shared and democratic learning. A “buddy system” (where learners get to choose their “buddy” for the whole law school experience) might help, too.[5] (Below this post are links to selected articles/research looking into more innovative teaching of law.)

For those who wish to focus on litigation, learners and faculty can then develop “clinics” and mock trials. However, not all learners need that. Certainly, everyone could join a few clinics, but it’s not a concentration that everyone would like to do. This could be true with others. However, joining these clinics, mock trials, workshops/writeshops, etc. must be voluntary, too. With the right mentorship and support, every student shall be nurtured to follow his own path.

As Bajpai and Kapur (n.d.) said,

“Law teachers need to be multi-modal in their teaching and should reduce reliance on the Socratic dialogue and case method.”

Bajpai and Kapur (n.d.)

2. Creative thinking helps logical thinking. By using different methodologies, learners also enhance their creative thinking—which is important in ‘connecting the dots.’ They become more motivated to study law because, now, they see it as another way to expand their creative thought process, which is useful in decision-making and policymaking.

3. Responsive and relevant grading system. The grading system must be useful as a tool in helping all learners excel and not to segregate them between “high performers” and “low performers.” Pasley (2016) has raised this important concern:

“Much of the anxiety and stress experienced in law school is directly related to the competitive and ambiguous nature of the grading system. One major reason grades do not reflect student understanding or effort is because exams fail to measure it. Exam-taking is a skill that is not used in legal practice and that is essentially useless to students outside of law school and the bar exam. Systems of grading should qualitatively tell a student what they are doing right and what they need to do to improve.

The current grading system leaves students guessing at how to improve, and frustratingly ignorant of what they are doing correctly. This lack of relevant feedback causes speculation, and increases the sense of isolation and hyper-competition that are toxic for community-building.Grades should not be based solely on end of the semester exams; they are not useful to students. The curve, which creates a general atmosphere of competition, exacerbates this frustration (NLG Radical Law Student Manual) by constantly ranking students based on a vague and unexplained system of evaluation and grade assignment. As Duncan Kennedy writes in his famous critique of legal education: “Law schools teach these rather rudimentary, essentially instrumental skills in a way that almost completely mystifies them for almost all law students…students don’t know when they are learning and when they aren’t, and have no way of improving or even understanding their own learning process.”3

Pasley, 2016

If grades are to be useful, they should tell students if they understand something correctly and how to understand it better, not where they fall in an arbitrary ranking system. Offering classes with pass/fail credit is one way to take the pressure off of students, especially in their first year. This allows students to take risks in classes they might otherwise avoid for fear of a bad grade. Making the first year all pass/fail [6] would be a useful reform, since it would immensely lower people’s stress levels and substantially improve the school environment. [7] (emphasis, mine; citations used are in the actual article by Pasley)

4. Use of both synchronous and asynchronous modes of learning (with no bias for each). All Zoom/online classes must be recorded (and lectures/powerpoint presentations uploaded in the LMS/Canvas) so that those who were absent could still enjoy the classes they missed. They could still catch up, in their own time. That is why it is important to allow asynchronous modality. Those who could attend mostly asynchronously only must not be disadvantaged.

The relevance, functionality, and advantage of online learning are highlighted here. Technology must not become a barrier but instead become a valued tool for more inclusion. Learners who are looking on their PC screens or have not memorized the law verbatim must not be chided. What is more critical is they truly understood the provisions and could explain and apply them in their own words. (It’s not illegal to bring notes and case briefs inside court rooms or in the halls of Congress.)

It’s not just because of pandemics that we need to innovate; the lingering problems in the justice system have long been here even without pandemics. It’s time to overhaul the law pedagogy and culture.

5. Voluntary and democratic engagement in class to ensure higher learning efficiency. Side-by-side with use of more innovative methods is a more democratic and respectful learning space. For example, the discussion of cases (e.g., 1 case per student) must be purely voluntary (volunteered the week prior to the next class). In a way, this is like a group case study (without cold-calling), which allows insightful and free-wheeling dialogue (not “grilling”), with the whole class participating. Hopefully, there will only be 5 ‘reporters’ per class (if it runs for 3 hours). The rest of the class may be used for a free-wheeling discussion.

6. Productive and engaged listeners and learners. This allows learners to be productive and good listeners. Because the “pressure” of cold-calling was removed and learners are treated as adults (and partners) then all of them will be able to really listen well to the 5 case discussants. That’s 5 solid cases per week (20 deeply understood cases in a month)—a productive listening/learning experience—compared with not even listening anymore because students are just too preoccupied for the “rehearsal” and the need to “perform.” Because no matter if the teacher is respectful, it will always be an embarrassing moment if one who was not very prepared (because of valid reasons) or will just attempt to “swim” madly in a sea of 15 cases—ending up simply blabbering (result: wasted time, stressed nerves, anxieties for all—because who wants to watch anyone having a less-than-enjoyable time?).

The 4 x 4 (or 5 x 5) Pathway in Law Pedagogy*

Moreover, the 4-year learning could be properly sequenced, following a logical learning pathway. For example, the acronym “RL-RrAD” or RL-RrAD–C (for the 5-year course) may help remember the focus for each year:

- Year 1 – Reading & Listening

- Year 2 – Research and Writing

- Year 3 – Analyzing

- Year 4 – Delivering

- Year 5 (optional) – Community service (and review for the bar)

I am developing this into a full-blown law curriculum–for its eventual adaption in Integrity Institute–so a citation is requested. This proposed curriculum will not use Socratic cold-calling but internships, clinics, mock trials, one-on-one counseling, and similar methodologies. It is also inspired by the concept of “keystone” species in ecology. Year 1 is the foundation stage; it should be a time for reading and listening.

In this kind of phasing and structuring, the mind (and how it works) is being prepared well. One does not teach how to drive a car by making the student drive one on the first hour. First, the instructor tells the student-driver to get to know the parts of the car (and how each one works), read a manual on traffic regulations, watch YouTube, etc. If the teacher simply wants to wait for an accident to happen, then he can ask the student-driver to go ahead and drive without giving him the needed preparations. Driving instructors do not do it for student-drivers but in many law schools, apparently, this is the norm. Again, are we still wondering why 75% flunk the exams?

7. Formulating the right questions. The class then allows free-thinking and free-wheeling discussions, which allow learners to hone their questioning skills as well—they are really learning together because lawyers need to be good at asking questions. Asking the right questions usually lead to insightful discussions.

8. Deep reading, legal research work, and analysis. At home, learners read as much cases as they can but with more focus on 1-2 cases only per class (by heart). This “deep learning” and research is better than trying to whack their gray matter with a long list of 15-20 cases per subject (an almost impossible feat with working students). Many learners or most of them are working—and, more importantly, their work is their classroom, too. Their work could be part of learning inside the classroom, too. They could share their experiences.

9. Importance of excellent case writing. Before the semester ends, learners will know whom among the class were not able to give a report yet. They will then be required to submit case digests instead (which everyone will get a copy of and edit/enhance as a team). Again, nothing is wasted. In fact, as the work of Pasley (2016) shared,

“Other graduate programs are also more invested in teaching their students excellent writing skills; law schools should integrate legal research and writing into every course. These methods can easily be adapted to legal education and provide an opportunity for more critical analysis and productive teaching styles.”

Pasley, 2016

10. Owning the future by taking care of the present. Naturally, learners have the obligation to read all of the assigned cases in their own time and pace. They can even suggest new /alternative cases. They can then use their weekends and summer or Christmas breaks to catch up. The toxic, one-way, adversarial, and patriarchal treatment will be removed and will be replaced with a collaborative culture and learning pedagogy that encourages a life well-lived–allowing time for enjoying family time, engaging in arts or sports, and opportunities for deepening mindfulness and spirituality. This allows learners to enjoy a balanced life–deepening their pursuit of learning and excellence as part of their contribution to the co-creation of a high-integrity future.

Learners could not be the great and responsive lawyers of the future if they are simply stressed out or leading unhealthy lifestyle. The growing cases of disbarment, corruption, and lawyers themselves violating the very same laws that they need to protect–all of these are writings on the wall. This is the time for reforms. Learners are not law students only; all persons in the classroom, even the professors, are “bearing their own crosses”. It’s a hard life, as it is. Law learners could excel under their teachers’ strong and nurturing wings and still live balanced and fulfilling lives.

Clearly, at the core of law education are integrity and ethics. How could law schools and educators really ensure that these law learners will be the good and high-integrity lawyers that the society expects them to be? How could the education system ensure that they will not ever “get lost in the system” and sell their souls in the process?

The first step is to allow them to co-create their learning pathway. Let them be heard. Allow them to participate in the co-creation of a society that is truly fair, honest, and inclusive.[8] Let them build their dreams as they also support yours; let them co-build the future of this country—in an atmosphere of inclusion.

Therefore, law schools–through LEB’s excellent, innovative, and exemplary leadership–can move with the times and gear toward more innovation (adapting with the new normal, too). Educators and fellow law students–today is a perfect day to begin co-creating a more innovative, responsive, and inclusive learning law pedagogy and culture.

Shall we, as one body, as true

partners, heed the challenge of Dean A. Ditucalan, when he said, “We are

rooting for you to build a new culture of teaching the law”?

End notes

Just to reiterate—this is not to criticize any law school or faculty. This is not a contest of finding out “who is better.” Learners still need ‘to eat more rice‘ when it comes to law mastery but there needs to be an appreciation that adult learners are co-creators and deeply invested and have a lot to contribute. It will be unfortunate if they are misunderstood and the response becomes defensive. It’s not a fight against “traditions” and faculty “expertise”. Those who see the positive will treat it as it is–a call for collaboration and partnership.

On this note, and as shared earlier, I am establishing Integrity Institute and, in the mature stage, law education shall be one of the program offerings [6]. If you are a law student or educator who also believe that the reforms in pedagogy must start now, please reach out.

Mabuhay po tayong lahat!

Footnotes (I typed this post from MS Word so the numbering of the footnotes may not match correctly. I will fix errors as soon as possible.)

(1) As indicated above, one of the core initiatives of Anna’s Trees & innovations OPC is Integrity Institute.

(2) Guest lecturers may be invited—they don’t even have to be lawyers all the time. Lectures are still very much needed because learners truly want to learn from their mentors and “soak up” their real-life experiences.

(3) S/he will be the partner-learner; the one who will check on the other (and be checked on reciprocally) every now and then.

(4) Adapted from the vision and teachings of Dr. Martin Seligman, Director of the Positive Psychology Center (University of Pennsylvania) and leading authority of positive psychology. More info is available here. Dr. Seligman’s profile is available at https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/people/martin-ep-seligman

(5) I personally do not agree with an adoption of a “pass/fail” grading system across-the board but an ideal scenario is to allow, for example, first year students to decide whether they wish to be given a “pass/fail” grade per subject, meaning, they have the option and liberty to choose which among their subjects are potential ones for the adaption of the pass/fail system. These students who opted for this adaption should still qualify for honor systems and scholarships.

(6) The current corporate structure shall be amended to allow the conversion of the Institute into a full-pledged school. Alternatively, a new corporate structure will be registered solely for the learning institute. In the meantime, we are developing a pedagogy and curriculum and hopefully have a chance to collaborate with an established law school that can host the program at least in the preliminary stage (or the first 2-3 years).

Sharing here some inspiring articles, which I think will ‘excite’ and allow an appreciation that this is truly a ripe time for change and innovations. Of course, this is being shared in the spirit of good faith and collaboration.

‘Socratic’ Teaching Is a Thing of the Past

Why Alter the Socratic Method?

Former Law Prof Says, ‘The Socratic Method Is A Sh**ty Method Of Teaching’

The fact that some students manage to figure out the Socratic method is no reason for professors to pat themselves on the backs

Socratic method linked to female underachievement in law school

The Socratic method has more problems than just being annoying

Reflections on Twenty Years of Law Teaching

MSU Law Dean says Socratic method in law schools ‘obsolete’

Innovative teaching methodologies in law: A critical analysis of methods and tools

Backwards Design, Forward Thinking

20 most innovative law schools

Future Law School. What Does It Look Like?

____________

Full disclosure/update: I began pursuing a Juris Doctor degree but had to stop due to my work load. I have long years of experience in policy work, development and environmental management, capacity /curriculum development, and knowledge management.

Mama Earth loves you: This is not a paid blog. I do not request for donation to maintain this blog but please make our tribe and Mama Earth happy by planting a tree (or trees!) on your birthday/s!

Leave a Reply